This is a topic I’ve discussed with colleagues on several occasions, and most recently in a really engaging thread on twitter: When is a grave…no longer a grave? If ever, at what point might that happen? There isn’t one definitive answer to this question, and the understanding of a grave, its significance, and longevity are rooted in our backgrounds, cultures, and society. I’ve finally found some time to sit down and write up the results of the discussion, and share some thoughts with you all.

The historic town of Fisherville, in the east Kootenay region of southeastern British Columbia, sat high above the Wild Horse Creek. Gold was discovered in these waters in the 1860s and in a typical boomtown style, around 5000 individuals very quickly made the area their home. Gold mining in Fisherville was very interesting, conducted at the creek by hydraulic mining the fold from the cliffs with high pressure hoses. The scars from the high pressure water blasting can still be seen today. Fisherville was home to many Chinese miners, who lived and died in the community. They were buried in their own burial ground, separate from the white settlers, and eventually all of their remains were repatriated from the historic site. The site has significance in the province as an early gold rush boom town, and Chinese-Canadian settlement after the gold rush craze died down (Heritage BC n.d.). Today the Chinese burial ground at Fisherville is marked with a sign on the interpretive walking trail, but the ground contains only depressions of where the bodies were once buried and an outdoor altar on the hill.

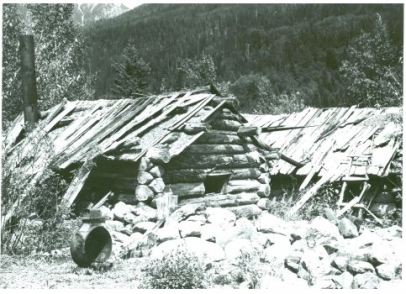

Cabins at Fisherville (Fort Steele Heritage Town, Heritage BC n.d.)

The site is commemorated as the resting place of these miners and settlers who came to the Kootenays in the gold rush of 1864 to seek their fortune with the rest of the population. Visitors read the sign, consider the burial site, and keep walking. We label and refer to the site as a burial ground, a cemetery, but does it still act as such if bodies themselves have been removed? While the graves themselves are empty holes in the ground, they represent the resting places of the Chinese people who were trying to make their fortune during the Kootenay gold rush and the difficulties they faced, both from the environment and from fellow settlers. In short, they are still graves and are remembered as such.

The act of commemoration of the dead is seen throughout human cultures across every country on earth, and burial has always been a popular mode of body disposal. Even those who died early during the Franklin Expedition were given a burial with a marker above the Arctic Circle, honouring the traditions of where those men had come from (Check out the photos in this article if you haven’t seen them before. Warning, there are human remains). Humans follow traditions, create new ones, read about and study what people did in the past, and explore options for our future dead. But what happens when the grave is no longer fulfilling its roll as a place for the body to rest and decompose? Does that time ever come?

Final results of twitter poll conducted in Feb 2019.

I conducted a twitter poll recently, expressly stating in the post that I was working on a blog post on this topic and was interested to hear everyone’s opinions and thoughts on the matter. I got replies from individuals of many backgrounds, and 281 votes on the questions presented here:

Unfortunately twitter only lets you do 4 options for the poll, but the answers are very interesting! A very small percentage of people said that a grave is no longer a grave once the body has fully decomposed. That would be hard to determine without excavating the space in some way to examine exactly how much of the person was left, and even then it is based on your definition of ‘gone’, whether social/cultural or scientific. In my experience excavating very poorly preserved historic burials in Newfoundland, I would hesitate to consider a decomposed body in a grave to no longer be present. The individual’s physical body has decomposed, for sure, but their organic material has become part of the sediment around them, changing the make up and chemistry of the very earth. If you study insect activity in soil, you could tell that a human body decomposed in that very spot. By examining the texture and compactness of the soil, you can sometimes tell where an individuals legs became clay.

Even after the body decomposes, the ground they became part of is effectively still the site of a human. Tom Cuthbertson (@tcuthbertson13 on twitter) informed me that in Virginia, “cemetery restoration projects [he’s] worked on are often forgotten (no longer being cared for), and most of the remains are fully decomposed with only an organic stain left, but you still need exhumation permits…also the soil from the coffin level is still considered remains, and is reinterred.” They are, in essence, there in the earth. In fact, materials from decomposition can leech into the soils below, effectively including the individual in the soil around them.

@DedInconvenient on twitter asked whether through the process of human composting being developed in Seattle by Katrina Spade, founder of Recompose, the concept of a grave changes. I would suggest that it does not, as the bodies being composted are not buried with the purpose of having an eternal resting place. Furthermore, they chose to have their body undergo this process after death, so whether the ground they become is still considered human or not is besides the point.

The second to last choice was that a grave is no longer a grave if the bodies have been removed. While if body is moved to a new location, their new burial place is arguably a more significant location, the original site of their burial still holds meaning and significance to individuals in the community, as with the example of the repatriated remains of the Chinese miners. Tanya Marsh (@TMAR22 on twitter) said that, in America, “the law says once ground has been committed to burial purposes, it is perpetually dedicated to that purpose…[it can be decommissioned] if all the graves are moved but it takes the consent of a court and usually living kin of those buried there” (Feb 5, 2019). As we know, burial grounds are excavated and moved all the time as part of infrastructure projects around the world (take this ongoing excavation at a historic burial site in London, for instance). The sites are recorded in the archaeological record as a burial place, so the record stands even after the bodies and sediment have been removed in favour of a highway or train tunnel (some regions call this a ‘legacy site’). Perhaps no longer legally a grave, once the site has been decommissioned legally as such, but these spaces often retain their social value as the “final” resting place of many individuals. As we’ve seen above, whether a grave is still present in this instance may different between individuals or groups.

54% of individuals who took the (informal) poll on twitter felt that a grave is never not a grave. This includes graves that have decomposed, have the bodies removed, been cut through by later buildings/pipes/roads/etc., or graves that were dug purposefully but never held a human body. If the earth was dug with the intention of containing human remains, the resulting hole is a grave. In some cases we find empty grave shafts in burial grounds, in the sense that a body was never buried there, not that decomposition is complete. They could have been dug ahead of future burials to save time, or perhaps even before the winter to accommodate burials without having to dig through frozen ground. While unused, they are still referred to as grave shafts . Accounting for both social and scientific reflections of burials, a grave always being a grave withstands degradation.

Grave of KĀPEYAKWĀSKONAM (photo from findagrave.com)

A wonderful example of the longevity of a grave was brought to my attention by @watching_crows, who said “KĀPEYAKWĀSKONAM, (Une Fléche) Chief One Arrow, was buried at St Boniface – I played on his grave as a child – the burial grounds have since been gentrified – in 2007 his remains were repatriated – I still visit his original gravesite – at that empty grave we share a connection.” While KĀPEYAKWĀSKONAM’s remains were removed from his grave and later repatriated, his original grave still holds significant meaning, and remains marked on the landscape so people will know where he was once buried. His grave, though empty, is still a grave.

One thought that was brought up by several individuals on twitter was that perhaps a grave is no longer culturally considered a grave when it is forgotten about by the people for whom it held significance, or if the social connection to that site is lost. I believe that in this case the significance of the site to the society which resides nearby could have been reduced or lost through history, but that doesn’t mean the graves themselves have vanished, just our understanding and knowledge of them has. There are many things beneath our feet that we aren’t aware of, but that doesn’t stop them from exisiting. Plenty of examples exist where gravestones or markers are removed from an area, and with them, the understanding that burials are still present in that space. The Guilford Green in Guilford, CT, is perfect example of this, as are sites in Ventura County, CA, and St. Oswald’s Playground in Durham City, UK. Here, gravestones have been removed and visitors may or may not be aware of the graves beneath their feet, but that does not mean they aren’t there.

What about when graves are recycled to make way for new bodies. Does that change the way we consider the concept of a final resting place? In North America, we are used to the idea that the grave is where your body will be *forever*. Unless your gravestone is removed, grave plots often are owned by the individual and/or their family in perpetuity. As I’ve written about before, this is not always the case, especially in places with a lot less undeveloped land than we have in Canada and the USA (undeveloped here being without contemporary or historic Euro-Canadian/American structures, not to say that Indigenous peoples were/are not still impacting and shaping the land).

Titanic at dock (Smithsonian).

As a closing thought, lets consider the RMS Titanic for a moment. The ship, which sank in 1912 with around 1500 deaths, rests at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean and is considered by many to be a grave site. While many of the bodies were not recovered and went down with the ship (two of my own ancestors included, brothers William & Frank Long), it is highly unlikely that there are bodies on the sea floor. Oxygen exists in the water, even at the depths the Titanic finally came to rest at, as well as deep sea life, which would have allowed for decomposition and breaking down of the bodies. Bodies within the ship, if they had no exposure to animals or oxygen, *may* still exist, but there is a heavy emphasis on the *may*, as those conditions are highly unlikely. Caitlin Doughty discusses this, as well as the concept of the sea floor being “human remains, or just mud” in her YouTube video on the topic. Some have tried to have the site classified as a grave or memorial site in order to protect the wreck, which has been countered with people saying there are probably not any remains left on the Titanic.

The question I’ll leave you with at the end of this extremely long blog post is this: Does it really matter if the remains are still there, to call the site a memorial/grave? They were there once, they died and ‘were buried’ there, in the ocean, and depending on your views on the longevity of a burial and human remains, a grave remains a grave, remembered or not.

(This has been a thought piece, as you can see there is not one direct answer to this question)

References

Find a Grave

2019. Chief One Arrow. Find a Grave. Available online at: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/17403744/chief-one_arrow

Heritage BC

n.d. Wild Horse Creek / Fisherville. Heritage BC. Available online at: https://heritagebc.ca/chinese-canadian-location/wild-horse-creek-fisherville/

February 27, 2019 at 10:13 am

Thanks Robyn for your contribution to the topic. Do you know if there is a trans-Atlantic difference in responses? Burial law here in UK is complex but straddles the N American & Continental traditions. In general, I perceive that public perception here is that a grave is forever – even though the law allows for ‘burial in perpetuity’ to be redefined as 75 years (25 years in Scotland) Again, public perception is that graveyards are forever, although many small public parks in our cities are ‘dormant’ Victorian burial grounds, cleared of headstones. (The law calls them ‘disused’, but this is a misnomer, as the remains are still there.) I have researched a number of exhumed and part-exhumed burial grounds, and found that property speculators start hovering as soon as the headstones disappear. The public’s reaction to this has always been conflicted but its rationale has changed over time; it should be set against the Victorian ambition of a ‘good death’ and sanitary scares of the C19th, contrasting with the war-hardened C20th, and now the more sentimental (post-Princess Diana) C21st with TV that shows daily murder and archaeology digs.

LikeLike

March 8, 2019 at 2:07 pm

Hi Colin, thank you for your comments on my research. My experience working with researchers in the UK and from mainland Europe is that the concept of a grave being ‘forever’ is more of a N.American ideal, where plots can actually be purchased in perpetuity (of course it might not work out like that, cemeteries are relocated, etc). It depends on what public perception of a burial space is, whether they deem it significant or special, to if it’s protected after even the headstones are removed. Language like ‘lost graves’ is used sometimes, even if no one really knows where they are other than understanding that graves are in X field somewhere.

LikeLike

Pingback: Canadian History Roundup – Week of February 24, 2019 | Unwritten Histories

Pingback: Ownership of the Grave: Who owns the Dead? | Spade & the Grave

Pingback: Chinese Miners’ Burials in British Columbia by: Robyn S. Lacy – Radical Death Studies