Hi friends, we’re back! This past Saturday we went out to New Perlican so I could give a little presentation to the community on my research in their burial grounds! It’s important for public archaeology that you actually tell the community you worked in about your research, so I was very excited to show off the maps and conclusions about my fieldwork surveys from the past 2 summers. I put together a little presentation showing the maps of the sides as well as several gravestone examples from each site to show everyone, and was able to tell them that we are going to be back in September to attempt GPR survey around St. Mark’s Cemetery to try and location the first Anglican church that was built in New Perlican. Stay tuned for that!

The purpose of my fieldwork and studying of these burial spaces was to take a closer look at the development of the burial landscape within a singular community, and how it has grown and evolved over the years, reflecting the community’s relationship with these spaces and mortality as a whole. We’ll also see some larger trends in burial spaces organization that are reflections of what we see in the rest of North America in the late 18th and 19th centuries. I also wanted to map these sites for the community, so that they would have a better record of gravestone location and site boundaries for future research and development.

Thank you to everyone who came out this weekend to see my talk and ask questions, it meant a lot! The projector was a little hard to see, so I’m happy to have this medium to share all the maps with you all!

New Perlican Burial Ground Map

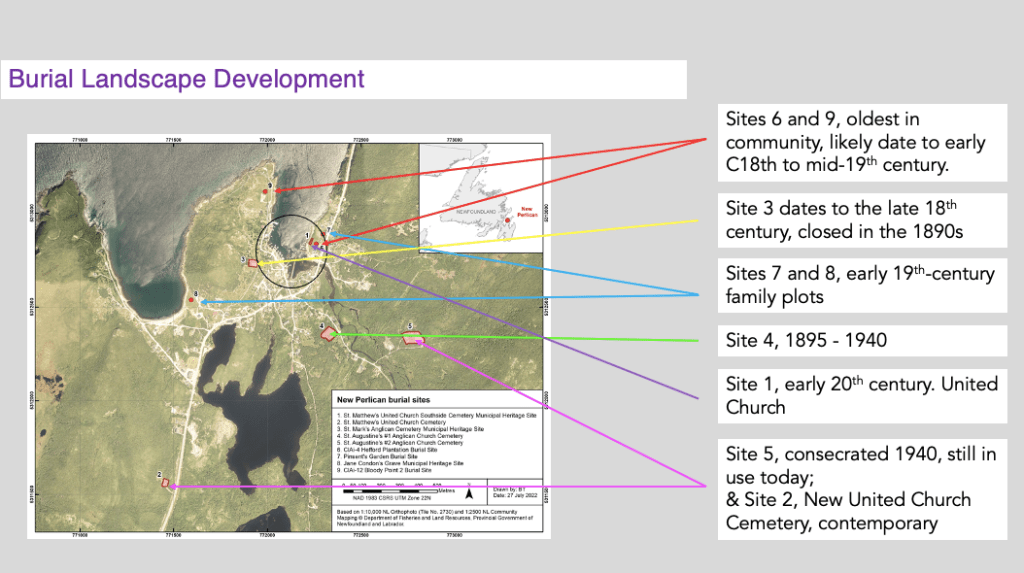

First we have the overview map of all the burial grounds within New Perlican. There are 9 sites in the town, which is wild for a place that only has about 200 residents according to the 2021 Canada Census. This is because the area has been home to European settlers and their descendants since 1675, when the Hefford family established their ‘plantation’ in the harbour (site 6). With 400 years of occupation came the need to establish burial spaces to house the dead as the years went on. For this project I did not look at sites 2 and 5, which are the modern cemeteries that serve New Perlican.

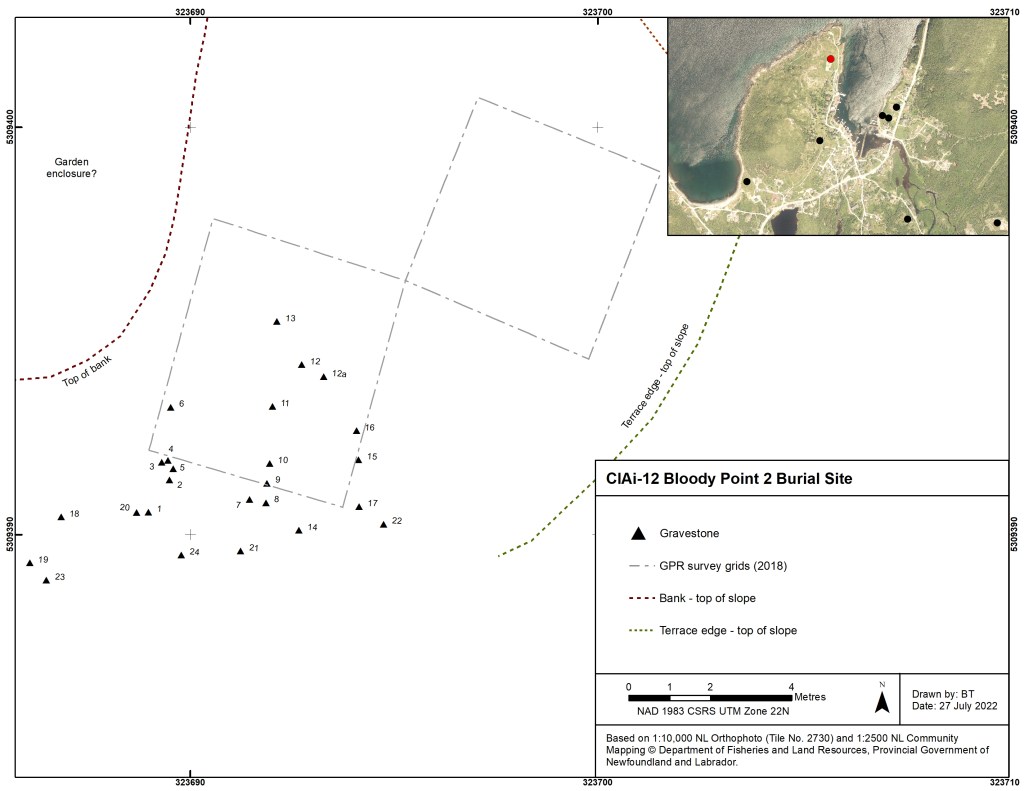

Bloody Point Burial Ground

The first site we surveyed was Bloody Point, which is a very interesting burial location in New Perlican. It was surveyed using ground penetrating radar in 2019 by Dr. Shannon Lewis-Simpson and Maria Lear, with the help of graduate students Rita Ujunwa Onah and Elsa Simms, in order to confirm that there were burials in the area. The grid they surveyed is represented on the map here by the two boxes. They identified 19 gravestones during this survey, and in 2021 we found several more for a total of 24 gravestones at the site. Out of these stones, only one had an inscription!

We also recorded surrounding features of landscape modification, such as root cellars, rubble piles from field clearing, and garden terraces. While the burial ground appears to be far from where the current centre of New Perlican, through the archaeological evidence it is clear that the burial space was once enclosed on all sides by areas of occupation and regular use. It was not isolated, and not forgotten.

Here are some examples of gravestones from Bloody Point. The large limestone gravestone on the left was the only one with an inscription on it, though most of it is illegible. There is a cherub or winged soul effigy at the top of the stone, with a partly exposed coffin and hourglass motif on either side, peeking up above the border. Because this stone is made from limestone, we know it was imported from Ireland or England, probably by a wealthy family.

The other stones are examples of field stones from the site, which have been roughly shaped and used as grave markers. You can see on the top one that it is rounded on the top, and has some tool marks as well. It is easy to tell when a stone is being used to make a grave, because it is typically made from a local slate or shale, roughly shaped, with its layers sticking up vertically. This doesn’t normally happen naturally, so if you see a stone sticking up like that in a graveyard, it was probably put there on purpose.

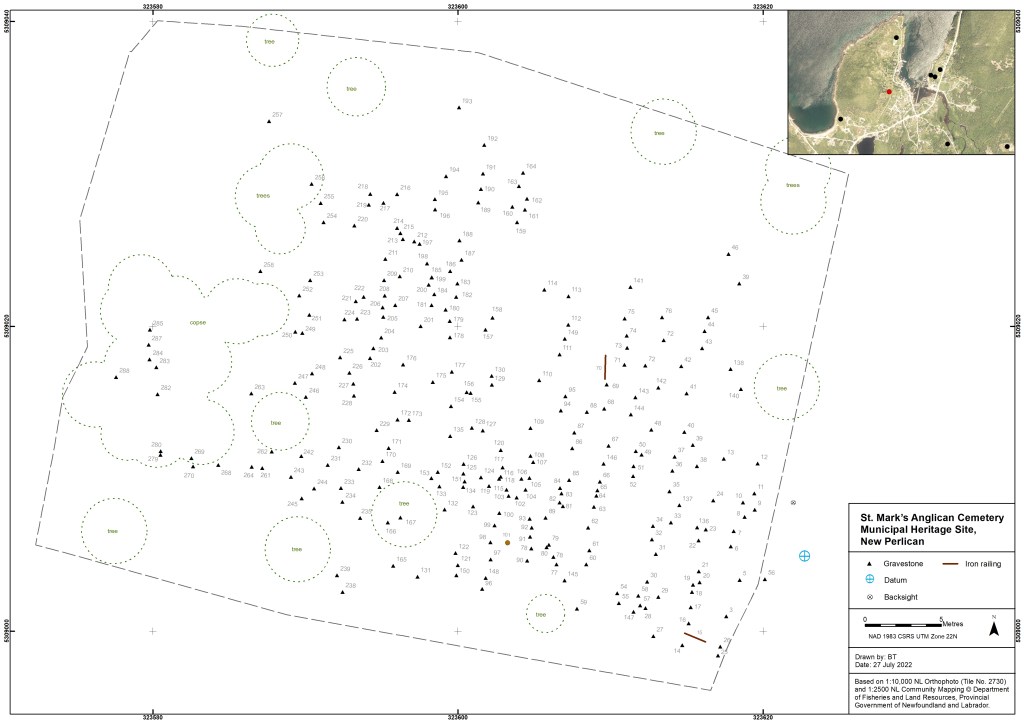

St. Mark’s Cemetery

At the St. Mark’s Cemetery, 306 potential grave markers were identified, double the number estimated before we started the fieldwork.The majority of those gravestones were field stones as well, with no inscriptions. You can see some lines on the map too which mark the location of several long iron rods that once made up a fence around one of the grave plots.

Below are several examples of gravestones at St. Mark’s! The stone on the top left is one of my favourites, it’s a field stone with no inscription, but a simple fish carved onto the top. In the middle we have a more formal gravestone to Albert Pittman. Below is the locally carved gravestone to Isabella Hobbs, a gorgeous example of local artistry.

The variety of gravestones at St. Mark’s is wonderful, and it’s definitely worth a visit if you’re in the area! This is also the site I mentioned that we will be doing GPR at, and so if anyone has memories or old photographs of the church that used to be nearby, myself and Heritage New Perlican would love to know!

St. Matthew’s United Church Cemetery & the Hefford Plantation

The St Matthew’s Southside Cemetery and the Hefford Plantation graves are very close together, but represent two distinct sites. St. Matthew’s did not open until the early 1900s and served the United Church, while the Hefford Plantation site, currently on private property, dates back to the 18th century, and likely contains burials from the 17th century as well, though this has not been confirmed through the archaeology.

St. Matthew’s cemetery is on the edge of a steep bank overlooking the harbour and is at risk of being impacted by the effects of coastal erosion, so documenting the number of and location of gravestones and grave markers at this site was particularity important for its future preservation. The Hefford Plantation is located on private property which we were given access to for surveying. There is one limestone gravestone there, and four field stones, although there may have been more in the past!

Here are some grave marker examples from those two sites. On the left we have a classic marble marker which is in excellent condition at St. Matthew’s, as well as a wood cross. The majority of the grave markers at this cemetery were wood crosses which had once been painted white. Several of them have rotted and fallen over, and were recorded where they were laying. On the right were have the late 18th century gravestone of William and Honor Hefford, decedents of the Heffords who first settled in the area in the 17th century.

Jane Condon’s Grave site

Then we recorded the Jane Condon burial site, which is located to the west of the other sites, on the east side of Vitter’s Cove on Gut Road. It was likely a family burial ground, consisting of one limestone gravestone and two small fieldstones. Jane died in 1816 and there were several burial sites established in the community at that time, which is why this was likely a family plot on private land. Personally, I think Jane’s grave has the best view of any of the grave sites in New Perlican!

These are all three stones at Jane Condon’s gravesite. I’ll take this opportunity to briefly talk about paint on gravestones. At the moment there is no paint stripper that is safe to use on historic stonework, so removing paint from gravestones is extremely difficult to impossible. This photo of Jane’s gravestone is after it was cleaned, and we only managed to remove a small amount of the paint that was already flaking off. The issue with paint is that it is not permeable to water, so it traps any moisture inside the stone itself, which allows it to crumble and break down faster. I really don’t recommend painting gravestones, especially not fully covering them with paint, from a conservation standpoint.

Pinsent’s Lane Burial Site

We also recorded the Pinsent’s Garden Burial site on Pinsent’s Lane. Unfortunately, we could not record this site using the total station due to the wood fence around the gravestones, so we recorded them using a handheld GPS instead. Based on their orientation, these gravestones have also been relocated, so they are not in their original context. Both stones are made from limestone and date to the early 19th century. They were imported from the British Isles. The map above was also made by Bryn Tapper in 2021.

St. Augustine’s Anglican Cemetery #1

Finally, the survey of St. Augustine’s Cemetery #1 took place in the spring of 2022. Low vegetation was not an issue for recorded fieldstones at this site, due to its ongoing maintenance by the neighbouring goats!

As this site was used more recently for burials, it was not deemed vital to record the location of all gravestones, as people were likely more familiar with this site. Instead, I focused on recording the fieldstones, after discussing the site with members of Heritage New Perlican and coming to understand that they did not know the number or extent that fieldstones had been used in their cemeteries. The survey took two days and resulted in the recording of 381 fieldstones, which were set out in rows like the more formal gravestones. It was very challenging to survey parts of this site due to the bushes and trees which required moving the survey rod’s height around several times to get through the foliage. This resulted in several phone calls with Bryn to make sure all the measurements were correct, but we got there in the end!

I did not end up taking photos of every gravestone surveyed at St. Augustine’s because they were all uninscribed fieldstones. Instead, I took some overview shots like this one, and pictures of the total station in action. On the right you can see Ian trying to level the total station, the most difficult part of using one, and my notebook with the coordinates of every point in it, which was used as a backup in case the machine’s memory was corrupt or erased. If it weren’t for the goats, there was no way we’d have seen all the fieldstones in the grass and bushes!

Burial Ground Development & Conclusions

So what does all this tell us about the burial grounds? Firstly, like many historic sites, there were way more gravestones than we were expecting to find, which means there are even more people buried below the surface. The gravestones we can see are usually only a fraction of the number of burials.

It is clear from the map above that there was a progression of burial spaces close to the community’s centre, outwards, from the late 19th century into the early-mid 20th century. Bloody Point and the Hefford Plantation graves, sites 6 and 9, are likely the oldest in the community, and date to at least the 18th century through the 19th. This is currently based on the surface evidence and documentary evidence from the Hefford plantation, but no excavation has or will be carried out.

Site 3, St. Mark’s burial ground, is extremely impressive and was at one point located next to the first church constructed in New Perlican. There is local interest in identifying the foundations of this church, and that is something I will be exploring further in my research, as its exacts locations are speculated but currently unknown. St. Mark’s opened sometime in the late 18th century, likely before the church was constructed, as was common in outport communities in rural Newfoundland. A 1828 newspaper detailed a travelling Bishop from Nova Scotia visited New Perlican and noted that there was no church constructed in the community by that time. The church on the site was around from approximately 1838 – 1842, and the burial ground was not closed until the 1890s, when site 4 was opened.

Then we see additional family plots, one of which is farther away from the town centre. This placement is more dependent on the burials being on private land, than the community burial spaces which were closer to the main dwelling area.

It is clear that overall, the older the site is, the closer it was to the central harbour live/work space in New Perlican. Today, the contemporary burial spaces that are still in use do reflect some older traditions, such as the use of field stones, but are also quite far from the central area, and out of sight from the roadways. This reflects the standard of moving burials out of community centres as older burial grounds were filled and closed, which is something we see across North America. This patterning/placement can be partially attributed to changing attitudes towards death in the British Isles and North America, leaning away from the memento mori towards a softening of death imagery and language through the 18th and into the 19th centuries, as well as community growth, and the rise of the rural cemetery movement.

So there you have it! Thank you again to everyone who came out on Saturday, and to Heritage New Perlican for facilitating and organising the afternoon. Thank you also to my supervisors, and to the Smallwood Foundation who funded my fieldwork and mapping for this part of my project. It has truly been an honour to help preserve the burial history of New Perlican, it’s such a special place!

Pingback: Holiday Diaries: Paris, Utrecht, & the Death, Dying, and Disposal 17 Conference | Spade & the Grave