Hi friends, it has been a minute since I’ve sat down to write anything on the blog! My last post was in May, and since then it has been a pretty busy summer with fieldwork, family visits, and a variety of trips! This winter, I’ll be updating our Black Cat fieldwork blog on some of the cool projects we’ve worked on, so keep an eye out for that HERE!

This August, we (my husband Ian and I) had the wonderful opportunity to travel to Utrecht to attend and present at the Association for the Study of Death and Society’s bi-annual conference, ‘Death, Dying, and Disposal 17’. Held in Utrecht and hosted by the Utrecht University, it looked like it was going to be a fantastic event, and my first DDD in person after presenting digitally a few years ago, so I was very excited. Of course, you can’t just fly all the way to Europe from Newfoundland and not add on a little holiday in there too, so we started off the trip in Paris! There were some excellent death studies related sites, so lets get into it.

Paris, France

The Paris Catacombs

Heads up: I will be including a photo or two from inside the Paris Catacombs below. I normally would not include images of any human remains for ethical reasons, but these remains are part of an ossuary which is meant to be visited and seen, and is cared for by the descendent community who allow access to the space.

I visited France as part of a high school EF Tours trip I went on in 2010, so I was really excited to see it again as an adult! We stayed in the 14th arrondissement, across the street from the Montparnasse Cemetery. It was a wonderful area, and a good location to access loads of gluten free bakeries…and of course the Paris Catacombs. The catacombs were one of our first stops on the trip, and I didn’t realize that they would have an audio tour included in the experience, so that was a nice bonus.

Rather than being natural caves, the catacombs were built inside the stone quarries carved out below the city for hundreds of years to create the buildings we are familiar with today. Of course, building on top of a rabidly expanding underground quarry lead to buildings starting to collapse, and work began in the 18th century to stabilize the caverns. As Paris began to run out of space to bury their dead, and a growing fear of illness from dead bodies arose from the public, the ossuary began to take shape as an effort to ease that tension. Also, a basement wall around the Holy Innocents’ Cemetery collapsed in 1774, and about a decade later, burials began their journey of exhumation to deposition in the newly established Paris Catacombs. In case you were wondering, a ossuary is a place of usually secondary burial, where the bodies of people who have been buried long enough to decay are then disinterred and reopened for a new burial, and their bones are moved to another location for mass burial, community remembrance, and visitation. This is not a practice in settler North American culture, but in Europe where there is much less land available for burials, it is normal, even today, to have 10, 20, or 50 year ‘leases’ on graves.

The city began moving remains from the Saints-Innocents Cemetery at night between 1785-1787, to avoid disturbing the public or causing outcry. The catacombs were open to the public for visitation by 1804, but interments continued through the French Revolution, until 1860.

We entered the Catacombs by descending a long, spiral staircase. I didn’t realize how far down we were really going until then! We had an audio guide that told us all about the restoration work to stabilize the old mines, and the history of the space, along with some exhibit panels as we approached the entrance to the catacombs themselves. As you enter the passages lined with bones, a door lintel warns the visitors “Arrete! C’est ici L’Empire de la Mort.” or ‘Stop! This is the Empire of the Dead’. Femurs and skulls made up the exterior walls, with the distal aspect of the femurs facing outwards, creating a relatively smooth surface. Skulls were used as accents to create patterns, including crosses, letters, and in one panel a heart. Behind these bone retaining walls were the rest of the remains, piled up and left to decay. The catacombs holds remains going back to the 10th century or so, as the ancient graveyards of Paris proper were moved into the tunnels.

It was a very cool experience to visit the catacombs. I’ve been to the Crypt of the Capuchin Friars in Rome, and will never forget that experience. Visiting human remains is not for everyone, but if you are interested in learning about the burial practices of early-modern Paris, and the history that the catacombs has in the city, it is definitely something I recommend doing! They have been a popular spot for visitors since the early 19th century…after all, coming face to face with your own mortality only helps you appreciate the life you have.

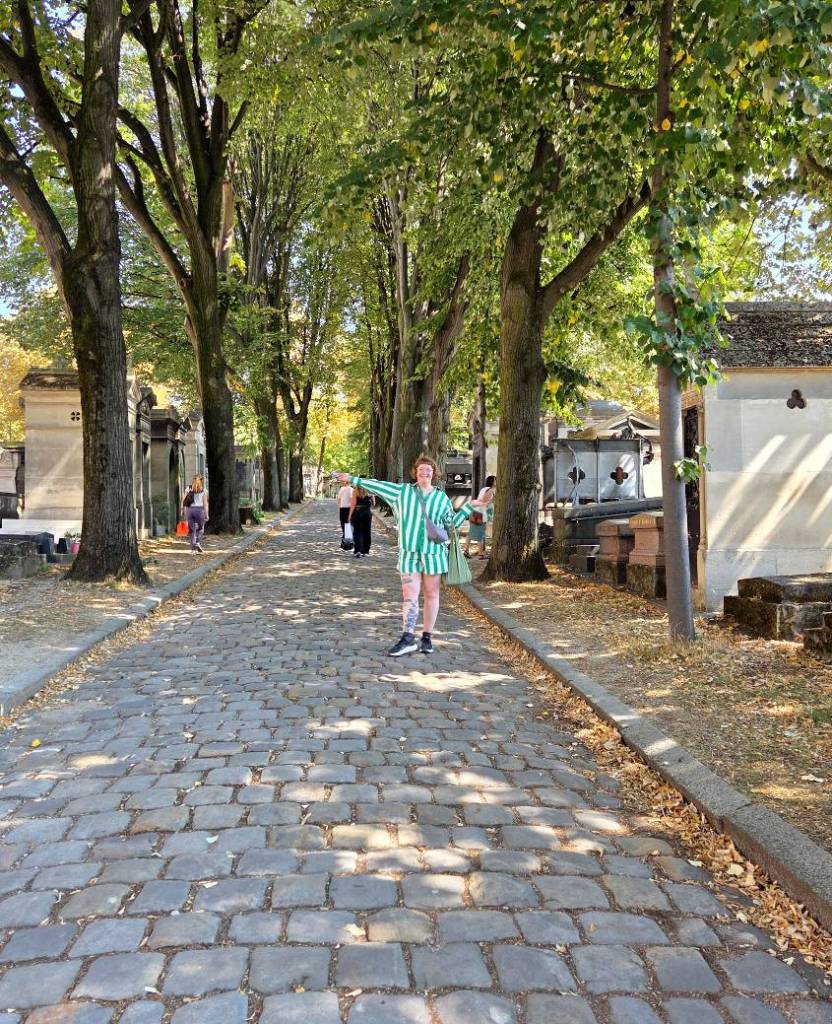

Pere Lachaise Cemetery

The other exciting location we visited in Paris was the famous ‘Pere Lachaise Cemetery’, also known as the very first rural garden cemetery in the world! The largest cemetery in Paris today, the site is located in the 20th arrondissement, and was also a municipal cemetery and thus non-denominational. The site opened in 1804 (same year as the catacombs! I just noticed that while writing this!). The cemetery was designed by Alexandre-Théodore Brongniart, a French architect, as a cemetery with wide spaces, trees, and unique monuments. It is still an operational cemetery today, and the Curator of the cemetery, Benoît Gallot, recently published a book on the site titled ‘The Secret Life of a Cemetery: The Wild Nature and Enchanting Lore of Pere-Lachaise’, which I highly recommend!

I was really excited to visit the cemetery, as the beginnings of the rural cemetery movement began there in European / North American settlements! If a burial site opened before 1804 in the global ‘west’ if we’re using that term, it should not actually be called a cemetery, but a graveyard or burial ground! Cemeteries as we know them today started here in Paris, at Pere Lachaise. The first municipal rural garden cemetery in North America was Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1831, and the first one in Canada was the Hamilton Cemetery in Hamilton, Ontario in 1847 (which you can read more about HERE). The Canadian site is closely tied with Mount Hermon Cemetery in Quebec City, Quebec, 1848, which is described as a garden cemetery. I’m off topic now

We bought a map for 2 or 3 euro on the way inside, and set off exploring. I think most people who visit the cemetery as tourists today are there to see some of the most famous residents like Jim Morrison (whose missing bust was recovered only a few weeks ago!), Chopin, and Oscar Wilde. I was excited to see Wilde’s grave, but I mostly wanted to visit because of the impact of the site on the development of burial sites in the 19th century.

It was 27.C while we were at the cemetery, but the trees throughout the site really saved us! Our first stop was Oscar Wilde’s grave, which is a stunning winged male figure in a sort of an art deco style, by sculptor Jacob Epstein. The cemetery had to put plexiglass wall around the grave to keep people from kissing it with lipstick on, as it was damaging the stone! As a gravestone conservator, I approve of this measure, the oils aren’t good for stonework at all. It was so amazing to visit the grave of such a significant literary figure! We had a wonderful time peeking into the family tombs, which were primarily little chapels, and the actual burials were below the structures.

We also went on a mission to find the grave of a man holding the face of his wife. I didn’t actually know this famous sculpture was at Pere Lachaise until our friend went earlier in the year and let me know! The unique grave is dedicated to Fernand Abelot, and his wife Henriette. I’ve seen a few sources online saying his ‘unknown wife’ about the woman depicted, but they are in fact buried together, having died in 1942 and 1967 respectively. It was so special to see these stunning monuments in a space that is very much still being used.

Utrecht, Netherlands + the DDD17 Conference

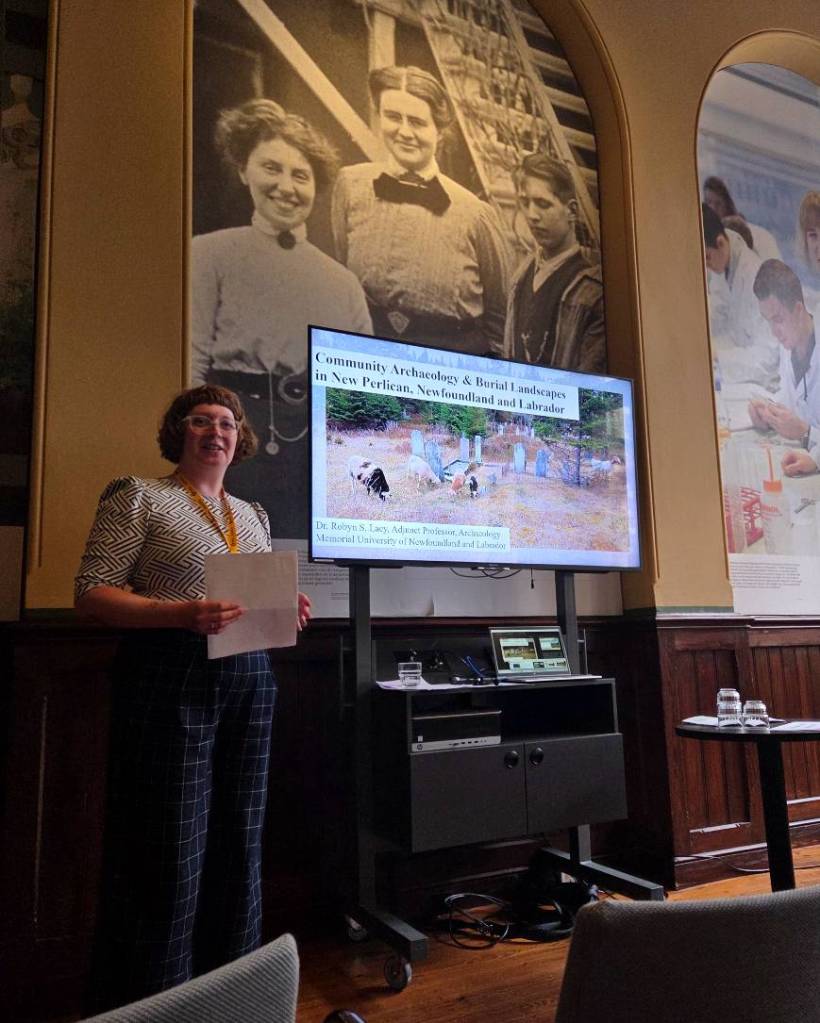

After Paris, we travelled via Eurostar to Amsterdam and then the local train to Utrecht for the Association for the Study of Death and Society’s (ASDS) bi-annual conference ‘Death, Dying, and Disposal’ (DDD). After the conference, I was informed that I was voted onto the council as a general member, so moving forward I’ll be part of the ASDS council! How exciting! The conference theme this year was “The Politics of Death”, which is a pretty interesting topic to consider, especially these days, and I was asked to be part of a session on community archaeology, from the new edited volume “Collaborative and Community-Engaged Archaeology” with Carolyn Dillian, Katie Clary, and Charles Bello as the editors. I have a chapter in this volume on my work in New Perlican, NL, the first portion of my PhD dissertation to be published! You can pick up the volume HERE, which is being released in a few days (December 16, 2025), from University of Florida Press.

The spaces at the University of Utrecht where the conference was held were wonderful, and I was really happy that we had the opportunity to travel to the Netherlands for this event! The conference had several sessions running at the same time across a few locations at the university, which all surrounded the famous Domtoren. The conference hub had a coffee station, artworks by Charles Clary on display, and a book room! Did I end up bringing seven or eight books home with me after the trip? Possibly. Did Ian offer me room in his suitcase for my books? Also yes! Titles I picked up included: ‘American Afterlife’ by Shannon Lee Dawdy, ‘On Grief and Studio Ghibli’ by Karl Thomas Smith, and ‘A Companion to Death, Burial, and Remembrance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, C. 1300-1700’ edited by Philip Booth and Elizabeth Tingle.

I don’t have any photos of the talk, but Ian and I also gave a talk about working with community heritage groups as gravestone conservators in Newfoundland and Labrador. We were able to include some examples from our project in Battle Harbour from this summer, working with the Battle Harbour Historic Trust, as well as some of our longterm projects such as Greenspond and Trinity. We had some interesting questions, and it was really cool to be able to present work we are doing in Newfoundland to researchers from around the world. Thank you to everyone who came to our talks!

We were mostly at the conference during our time in Utrecht, but were able to visit a few spots around the city including the historic Domkerk and climbed the Domtoren, wandered the canals (will someone please invite me on one of those boats with the tables for drinks next time?). We also went on a walking tour organized by the conference about the connection of the City of Utrecht and the Atlantic slave trade. It was really informative, and if I am successful in my postdoc application in the new year, will be a very useful resource for my upcoming project.

In the Domkerk, constructed in the 13th century, we were able to view a number of ornate stone ledgers marking the graves of prominent members of Utrecht society. So many of them had memento mori imagery on them, common in the medieval period. The one pictured here, from 1565, shows a skeleton on an altar or plinth which reads ‘memento mori’, flanked by two heralds. A winged cherub head, another common memento mori symbol, can be seen on the altar. Below, a cherub rests on a box reading ‘Pavi Atim’ or ‘I was so happy’ in Latin. I’d love to go back and take a closer look at the details on some of those monuments.

This has been just a highlights reel of some of the death studies related things we saw on this trip! We also spent a lot of time looking at art and historic buildings, eating amazing food, and walking for ages to explore the cities we were visiting. I’m already looking forward to going back, and for the next DDD conference. Thanks for reading!