If you are new to the study of burial markers and don’t come from a geologic background or have prior knowledge in basic geology, grasping the differences in materials found in burial grounds might seem like a monumental task! In this post, we will be discussing the composition and problems/perks of different stone types that are found across North American historical burial grounds, as well as common weathering issues that can be seen across these stones. I do my best to keep this post up to date as I learn more about the geologic processes at work in our historic cemeteries and graveyards.

(last update: December 4, 2023)

Firstly, this post will be dealing with gravestones in the most specific of the sense. There are, of course, many different types of markers for a grave. Some are made from wood (biodegradable), ‘white bronze’ monuments made from zinc, cast-iron, cement, and more! Each one of these materials comes with its own pros and cons, but we won’t be discussing them in this post. As a sometimes geoarchaeologist, I’m primarily here to talk about rocks.

The impression that people get from a stone monument goes hand in hand with the ideal of the ‘immortal resting place’ that surround the grave, particularly in North America. I discussed the idea, in a previous post, about understanding and allowing the decay of structures of objects as part of their natural life cycle, and this goes for gravestones too. While I wholeheartedly support monument conservation on gravestones where it makes sense to do so (i.e. the stone is in ok condition but has cracked in half and can be repaired vs. a degraded stone that is in poor condition and additional damage could be done by trying to ‘restore’ it), there is a somewhat of a line that means some things will be left to decay. And you know what? That’s fine. Nothing on this earth is permanent, and in a burial ground or cemetery is certainly the place to remember that.

There are three types of weathering that effect gravestones: Chemical, Physical, and Biological (Historic England 2021).

- Chemical Weathering includes ‘disruption through soluble salts’, in which the stones draw up ground water and salt can be drawn into and crystallize within the stones (Historic England 2021). It also includes the effects of acid rain and pollution.

- Physical Weathering is the natural degradation of the rock through wind, rain, etc, as well as through freeze/thaw cycles.

- Biological Weathering details the effects of trees, shrubs, lichens, and vines of the rock, which can lead to damage to the surface and body of the gravestones.

Update: Earlier versions of this post stated that all of these processes were ‘erosion’, but further research and discussion from geologist colleagues has informed me that erosion is a different type of process than weathering. Erosion is the “removal of sediment such as sand, silt, or gravel, by wind or water…the actual moving of the particles that are created by the different forms of weathering”, while weathering is “the breaking down of rock material by things like heating and cooling, frost or crystal wedging, or chemicals, like acid in rain” (National Parks Service 2021).

Basically stones, like all things, wear away. But they can also last a heck of a lot longer than the bodies buried beneath them! Without further ado, lets discuss the geology, pros, and cons of common stone types you’ll encounter in historic burial grounds in North America. A lot of this information can also be applied to other countries, especially the British Isles and western Europe, but all my examples will be from North America.

Sandstone: This material is a sedimentary rock which is comprised of sand grains (0.06 – 2mm) which have been compressed together to form a solid rock. The make up of sandstone varies based on the materials inside, with some examples having a very high quartz content, with others having lots of feldspar or other materials. High quartz content is an indication of a mature sand. Sandstone is fairly porous. They are clastic in origin, rather than organic (think chalk) or chemical (jasper), and the materials which hold the grains together are typically a calcite, clays, and/or silica. While the grains themselves might be quite hard, the material between them is softer and prone to faster weathering

Gravestones made from sandstone are easier to carve than a harder material, but this also means they often exhibit poor weathering resilience, resulting in lamination or exfoliation causing large portions of the stone to fall off, blistering of the stone surface, discolouration due to soot or a reaction between sulphur dioxide and calcium carbonate, and the effects of lichen growth and vines using the calcium carbonate in the sandstone as a food source (UCL 2019). These reactions can be stabilised by conservation techniques but not reversed.

Limestone: Another sedimentary rock, limestone is made up of at minimum 80% calcium carbonate (CaCO3), which is ‘prone to dissolution by acid rain, a week carbonic acid’ (UCL 2019). The high CaCO3 content in limestone is due to the skeletal fragments of marine organisms which make up the material, such as corals and shells. Some forms of limestone have visible fossils in them, but the majority of the fossils are tiny fragments of organisms, as well as containing silica, and often sand, silt, and clay. It does not contain grains.

Limestone is particularly susceptible to chemical weathering due to the relatively soft nature of the rock. Gases in the atmosphere such as sulphur dioxide, which often result in a loosening of the exterior of the stone causing loss of material (‘sugaring’) and the formation of a black crust in locations with higher rates of pollutants. Due to the high CaCO3 content in the rock, limestone is also a favourite of vines, lichens, and mosses, which anchor into the surface by eating into the calcium, both physically altering the surface of the stone and trapping water inside. (by no means should you pull vines off a gravestone, as it will pull portions of the stone off with it. Let an expert deal with vegetation safely!)

Historically, limestone has often been referred to as marble in many instances. Stone masons have long called limestones ‘marble’ as a catch all term, but that does not mean they are the same geologically. This is likely due to the similarity in appearance between the materials in many examples, and the fact that marble is created when limestone undergoes metamorphism, a process in which an igneous or sedimentary rock undergoes intense heat and/or pressure, changing the chemical composition of the material itself. It creates a new rock, one that is completely different from the rock that helped to form it. As a result of the metamorphism, any existing visible fossils are destroyed and are no longer visible. This is often the clear distinction between limestone or marble: if you can see fossils, you are looking at a limestone. An excellent example of this can be found in Durham Cathedral, UK, where the famous black columns within the cathedral are made from ‘Frosterley Marble’. While this is its common name, it is not the stone type which is a black limestone with stark white and cream clear fossils inside. The columns themselves are a sight to behold, and date to 1350 CE!

Marble: Marble dominated the North American grave scene through the 19th century, with their clear white faces gleaming throughout cemeteries and burial grounds. The stones are fairly soft and easy to carve, and were exported across the continent as a very popular option, including up to Newfoundland in the early-mid 1800s! As already mentioned, marble is a metemorphic rock comprised of carbonate minerals, created after limestone undergoes metamorphism (or dolomite, or other sedimentary carbonate rich rocks, but mostly limestones).

Pure-white marble gleams when polished, but after only a decade or so exposed to various weathering forms, the white surface becomes pitted and stained, and inscriptions begin to erode. If you touch a weathered marble, fine grains will brush off the surface (UCL 2019). Marble is particularly susceptible to acid rain and other chemical weathering due to its high CaCO3 content. They are also badly damaged if set into or repaired by concrete. Concrete traps water inside the material, rather than letting it escape through the porous stone, and results in weakened points in the stone with higher moisture content. This means they will weather faster, and break easier. It is never recommended to apply concrete directly to a gravestone, as it is extremely difficult to impossible to remove without damaging the stone in the future, and will speed up its degradation.

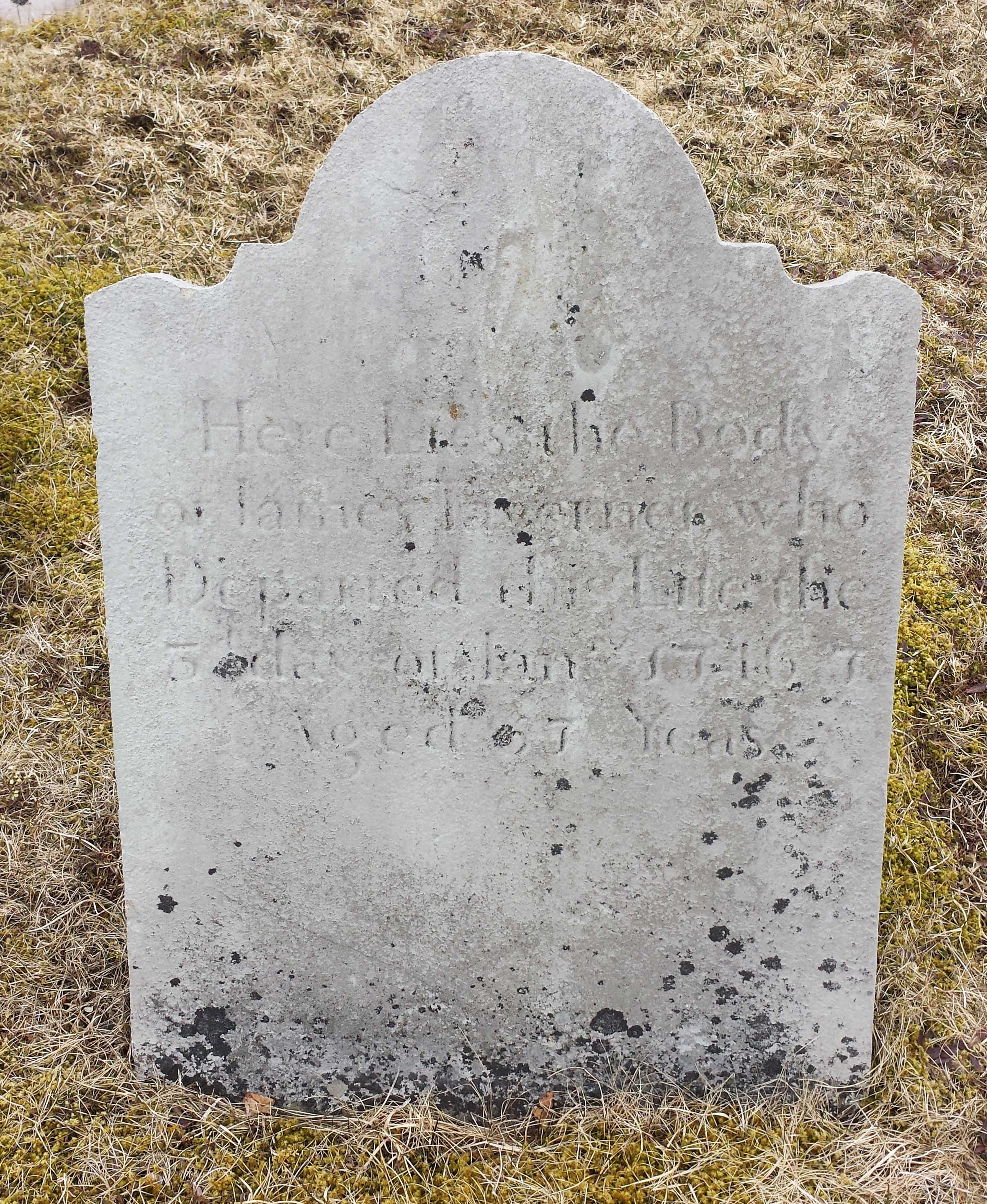

Slate: Slate is one of my personal favourite material types for gravestones. An extremely fine-grained, foliated metamorphic rock, slate is the result of shale (sedimentary) undergoing metamorphism. A popular building material, slate architecture can be seen across Wales, and in North America mostly in the form of slate roof tiles. The 17th century settlement of Ferryland, Newfoundland, utilized local slate and shale to construct their settlement!

As a gravestone, slate is extremely durable and great for displaying incised details for long periods of time. It is, however, still susceptible to lamination which causes the layers of rock to come apart. Often when this occurs, the text on the broken pieces shows very little weathering otherwise. This material is less common in North America as it is in the UK, but you can still find excellent, well preserved examples.

Granite: This rock gained popularity for gravestones around the end of the 19th century, and is the most common stone in contemporary cemeteries today. The only commonly igneous rock in the historic gravestone materials roster, granite is made up of quartz, feldspar, and other interlocking materials such a biotite. It is a very hard stone and has been used as a building material throughout human history due to its durability and low permeability. They have a high silica content, typically. On the Mohs Hardness Scale, the reference for geologic stone hardness (0-10), granite is typically a 6-8, whereas marble is around a 3, limestone is a 3-4, slate is a 3-5.5 depending on many factors, and sandstone surprisingly is around a 6!

Granite is labour-intensive to carve using hand tools, and the majority of gravestones we see today made from granite feature laser-cut inscription. In terms of weathering, polished granite surfaces have been seen to last for over 100 years without substantial give to weathering (Historic England 2021). However, they can begin to break down due to the deterioration of the silica within the rock (Historic England 2021).

Conclusions:

There we have it, the most common stone types that you’ll see within historic burial grounds in North America. Of course, this is not a catch-all list, and there are many types of rock that are used regionally, or variations in rocks and/ore environments that will change the way and rate that they undergo weathering. What is important to remember when recording gravestones is that while rock seems permanent, it isn’t, and you should always be careful when touching a gravestone not to lean against it, push it, or sit below a leaning headstone or table tomb, as you don’t know what state the material is in (and no rubbings or dumping stuff like flour or shaving cream on them either. Stop it).

I’m extremely interested in the way in which gravestones are subjected to weathering, and the effect of weathering on different types of inscriptions. Different affects of weathering on stones, and their conservation, is of special interest to me and why I went into gravestone conservation as part of my speciality.

If you have any questions or comments for me about common materials used to create gravestones, please drop me a comment below or send me an email! As always, thanks for reading.

If you enjoyed this, and my other work, please consider buying an early-career researcher a coffee? Link is in the right sidebar above! Thank you!

References:

Historic England. 2021. Caring for Historic Graveyard and Cemetery Monuments. Website: https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/caring-for-heritage/cemeteries-and-burial-grounds/monuments/

National Parks Service. 2021. Weathering and Erosion. National Parks Service. Website: https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/weathering-erosion.htm#:~:text=Erosion%20is%20one%20that%20most,chemicals%2C%20like%20acid%20in%20rain..

UCL. 2019. Gravestone Weathering. University College London, Earth Sciences. website: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/earth-sciences/impact/public-engagement/londons-geology/londons-geology-fieldwork/st-pancras-gardens/gravestone

May 11, 2019 at 9:19 am

Very interesting, reminded me of all the things I’ve forgotten from my Science classes. Do you have any recommendations for cleaning old tombstones?

LikeLike

May 11, 2019 at 1:43 pm

Thanks Suzanne! For cleaning, the easiest thing to do is just water and a soft-bristled brush. If the stone is eroding or starting to show the ‘grain’ texture, hard scrubbing just causes further weathering. Pulling off lichen & vines can damage the stone. Don’t use any harsh soaps or detergent either 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: This week’s crème de la crème — May 11, 2019 | Genealogy à la carte

June 14, 2019 at 7:56 pm

Hi Robyn and Suzanne: using warm water and vinegar works too. Always use a plastic brush and toothbrush to clean. Never use a wire brush! We tell our customers to be careful with those monument toppers with metal legs. Once rust gets on the granite, there isn’t anything that will take it off!

LikeLike

June 14, 2019 at 8:37 pm

I do not recommend using vinegar on stone. It is an acidic substance that eats into soft minerals & does damage in the long run. Soft brush and water or D2 biological cleaner are all you need.

LikeLike

January 5, 2020 at 8:28 pm

We are a group of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community.Your site offered us with valuable info to work on. You have done an impressivejob and our entire community will be grateful to you.

LikeLike

October 23, 2020 at 10:42 am

Hi Robyn!

As a midwest USA archaeologist I also restore cemeteries in between projects. Great read! The one I’m currently working on has several severely degraded marble headstones. There’s one in particular that is flaking off in big sheets; with dirt trapped underneath. Would you think it unwise to rainproof the cracks with finishing stone, thus trapping the dirt underneath but hopefully saving the text for several more years?

I’d love to hear your thoughts

LikeLike

October 26, 2020 at 11:32 am

Hi Elise, Thanks so much for your message!

Degrading marble is difficult because once it reaches a certain state of decay, there isn’t much that can be done. I would not suggest rainproofing the stone, however, as it would trap not only the dirt but also moisture within the stone, which would cause it to weather quicker. My best advice would be to photograph and carefully record the inscription while it is still visible, and make those records freely available.

Cheers!

LikeLike

Pingback: “Discussing Gravestone Conservation Digitally: Disseminating Data & Advice through Blogging & Social Media” #DigiDeath Online Conference | Spade & the Grave

July 11, 2021 at 11:16 pm

Hi Robyn!

I don’t have any background prior to Geology composition and gravestone ideas and its composition. Thanks for sharing this post, it really helps me to understand more about this topic.

LikeLike

June 7, 2022 at 7:52 am

A Conservation Commission member (Greenwich, CT) stated that it’s OK of fallen grave markers are buried by the ground while the group develops standards. Is this true, stones swallowed by the ground won’t cause damage.

LikeLike

June 7, 2022 at 8:40 am

As long as they know where the stones are, they won’t become damaged by being covered by the ground for s little while. However, some stones like marble are more susceptible to damage from plants, so that is something to consider.

LikeLike

April 16, 2023 at 3:01 am

Stones will erode quicker with earth contact. Especially the sharp corners. If the stones are broken this makes rejoining them more difficult after time. Also the engravings collect moisture when flat causing damage from freezing and thawing as well.

LikeLike

April 24, 2023 at 6:32 pm

You’re right! It will also weather from acid rain and wind! There is basically nothing you can do to stop it from falling apart eventually 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: How To Choose The Perfect Headstone Or Grave Marker – FuneralDirect

May 20, 2023 at 5:56 am

Would it hurt to put water sealer on a headstone

LikeLike

May 20, 2023 at 2:01 pm

Hi Dennis, yes it would! It would trap moisture inside the stone and cause it to break down faster. Any kind of sealers are not advised 🙂

LikeLike

December 1, 2023 at 6:38 pm

I love that you mentioned how slate is a very strong material for gravestones and works well for exhibiting engraved features for extended periods. Nonetheless, you said that lamination, which splits the rock layers apart, can still occur. I will consider this when my family picks a new flat grave marker for my grandma who passed away last year. Thanks for this.

LikeLike

December 8, 2023 at 2:36 pm

Thank you for your kind comment! Slate from New England or from Wales, if you’re looking for a marker, is the best quality I know of. It can split apart, but from my experience it rarely happens if the slate is of good quality!

LikeLike

December 13, 2023 at 12:24 pm

Hello,

Great article! I’m starting to look myself and i’ve always thought it interesting in our family cemetary (Virginia), the variations (degradation, lichens, etc) what i believe are granite headstones. In other words, through the typical generations (where it was marble, some sandstone, granite, etc)…what i find interesting is within what appears to be granite, some from 150 years ago look almost brand new yet ones from <80 have growth, hard to read etc.

Any comments on that?

Given other articles i've read (both from UK as well as Boston), it appears as though slate has held up best the test of time. Any comments on that?

Thanks in advance

Mark Miller

LikeLike

January 25, 2024 at 11:32 am

Hi Mark, thanks for reading! Granite is one of the hardest natural stones, so I’m not surprised to hear that they are weathering very slowly. Slate definitely also holds up very well, some of the best gravestones I’ve seen for legibility were in abandoned burial sites in Wales that were at least 200 years old, crisp as the day they were carved. Cheers!

LikeLike